2. Maintainability depends on modularity: Stop using namespaces!

Modularity is at the core of everything. Initially I had approached this very differently, but it turned out after ~ 20 drafts that nothing else is as important as getting modularization right.

Good modularization makes building and packaging for the browser easy, it makes testing easier and it defines how maintainable the code is. It is the linchpin that makes it possible to write testable, packagable and maintainable code.

What is maintainable code?

- it is easy to understand and troubleshoot

- it is easy to test

- it is easy to refactor

What is hard-to-maintain code?

- it has many dependencies, making it hard to understand and hard to test independently of the whole

- it accesses data from and writes data to the global scope, which makes it hard to consistently set up the same state for testing

- it has side-effects, which means that it cannot be instantiated easily/repeatably in a test

- it exposes a large external surface and doesn't hide its implementation details, which makes it hard to refactor without breaking many other components that depend on that public interface

If you think about it, these statements are either directly about modularizing code properly, or are influenced by the way in which code is divided into distinct modules.

What is modular code?

Modular code is code which is separated into independent modules. The idea is that internal details of individual modules should be hidden behind a public interface, making each module easier to understand, test and refactor independently of others.

Modularity is not just about code organization. You can have code that looks modular, but isn't. You can arrange your code in multiple modules and have namespaces, but that code can still expose its private details and have complex interdependencies through expectations about other parts of the code.

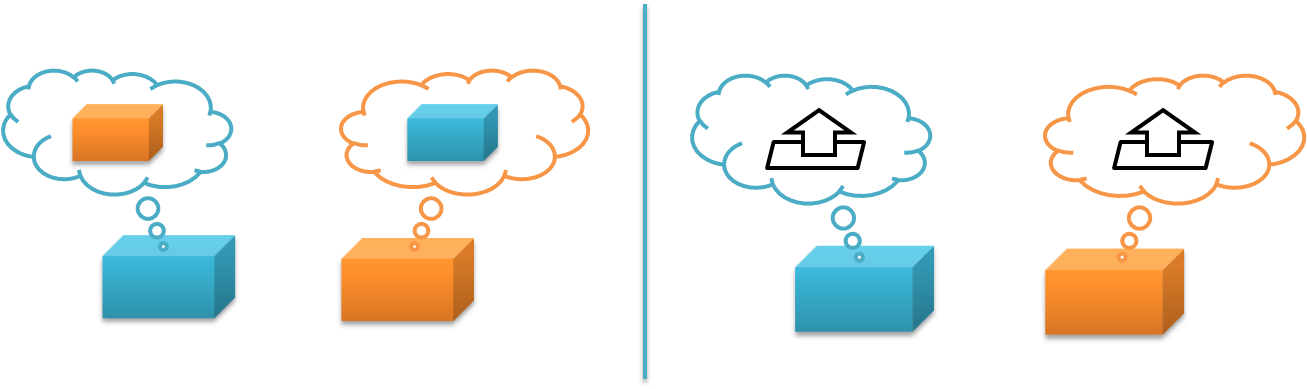

Compare the two cases above (1). In the case on the left, the blue module knows specifically about the orange module. It might refer to the other module directly via a global name; it might use the internal functions of the other module that are carelessly exposed. In any case, if that specific module is not there, it will break.

In the case on the right, each module just knows about a public interface and nothing else about the other module. The blue module can use any other module that implements the same interface; more importantly, as long as the public interface remains consistent the orange module can change internally and can be replaced with a different implementation, such as a mock object for testing.

The problem with namespaces

The browser does not have a module system other than that it is capable of loading files containing Javascript. Everything in the root scope of those files is injected directly into the global scope under the window variable in the same order the script tags were specified.

When people talk about "modular Javascript", what they often refer to is using namespaces. This is basically the approach where you pick a prefix like "window.MyApp" and assign everything underneath it, with the idea that when every object has its own global name, we have achieved modularity. Namespaces do create hierarchies, but they suffer from two problems:

Choices about privacy have to be made on a global basis. In a namespace-only system, you can have private variables and functions, but choices about privacy have to be made on a global basis within a single source file. Either you expose something in the global namespace, or you don't.

This does not provide enough control; with namespaces you cannot expose some detail to "related"/"friendly" users (e.g. within the same subsystem) without making that code globally accessible via the namespace.

This leads to coupling through the globally accessible names. If you expose a detail, you have no control over whether some other piece of code can access and start depending on something you meant to make visible only to a limited subsystem.

We should be able to expose details to related code without exposing that code globally. Hiding details from unrelated modules is useful because it makes it possible to modify the implementation details without breaking dependent code.

Modules become dependent on global state. The other problem with namespaces is that they do not provide any protection from global state. Global namespaces tend to lead to sloppy thinking: since you only have blunt control over visibility, it's easy to fall into the mode where you just add or modify things in the global scope (or a namespace under it).

One of the major causes of complexity is writing code that has remote inputs (e.g. things referred to by global name that are defined and set up elsewhere) or global effects (e.g. where the order in which a module was included affects other modules because it alters global variables). Code written using globals can have a different result depending on what is in the global scope (e.g. window.*).

Modules shouldn't add things to the global scope. Locally scoped data is easier to understand, change and test than globally scoped data. If things need to be put in the global scope, that code should be isolated and become a part of an initialization step. Namespaces don't provide a way to do this; in fact, they actively encourage you to change the global state and inject things into it whenever you want.

Examples of bad practices

The examples below illustrate some bad practices.

Do not leak global variables

Avoid adding variables to the global scope if you don't need to. The snippet below will implicitly add a global variable.

// Bad: adds a global variable called "window.foo"

var foo = 'bar';To prevent variables from becoming global, always write your code in a closure/anonymous function - or have a build system that does this for you:

;(function() {

// Good: local variable is inaccessible from the global scope

var foo = 'bar';

}());If you actually want to register a global variable, then you should make it a big thing and only do it in one specific place in your code. This isolates instantiation from definition, and forces you to look at your ugly state initialization instead of hiding it in multiple places (where it can have surprising impacts):

function initialize(win) {

// Good: if you must have globals,

// make sure you separate definition from instantiation

win.foo = 'bar';

}In the function above, the variable is explicitly assigned to the win object passed to it. The reason this is a function is that modules should not have side-effects when loaded. We can defer calling the initialize function until we really want to inject things into the global scope.

Do not expose implementation details

Details that are not relevant to the users of the module should be hidden. Don't just blindly assign everything into a namespace. Otherwise anyone refactoring your code will have to treat the full set of functions as the public interface until proven differently (the "change and pray" method of refactoring).

Don't define two things (or, oh, horror, more than two things!) in the same file, no matter how convenient it is for you right now. Each file should define and export just one thing.

;(function() {

// Bad: global names = global state

window.FooMachine = {};

// Bad: implementation detail is made publicly accessible

FooMachine.processBar = function () { ... };

FooMachine.doFoo = function(bar) {

FooMachine.processBar(bar);

// ...

};

// Bad: exporting another object from the same file!

// No logical mapping from modules to files.

window.BarMachine = { ... };

})();The code below does it properly: the internal "processBar" function is local to the scope, so it cannot be accessed outside. It also only exports one thing, the current module.

;(function() {

// Good: the name is local to this module

var FooMachine = {};

// Good: implementation detail is clearly local to the closure

function processBar() { ... }

FooMachine.doFoo = function(bar) {

processBar(bar);

// ...

};

// Good: only exporting the public interface,

// internals can be refactored without worrying

return FooMachine;

})();A common pattern for classes (e.g. objects instantiated from a prototype) is to simply mark class methods as private by starting them with a underscore. You can properly hide class methods by using .call/.apply to set "this", but I won't show it here; it's a minor detail.

Do not mix definition and instantiation/initialization

Your code should differentiate between definition and instantiation/initialization. Combining these two together often leads to problems for testing and reusing components.

Don't do this:

function FooObserver() {

// ...

}

var f = new FooObserver();

f.observe('window.Foo.Bar');

module.exports = FooObserver;While this is a proper module (I'm excluding the wrapper here), it mixes initialization with definition. What you should do instead is have two parts, one responsible for definition, and the other performing the initialization for this particular use case. E.g. foo_observer.js

function FooObserver() {

// ...

}

module.exports = FooObserver;and bootstrap.js:

module.exports = {

initialize: function(win) {

win.Foo.Bar = new Baz();

var f = new FooObserver();

f.observe('window.Foo.Bar');

}

};Now, FooObserver can be instantiated/initialized separately since we are not forced to initialize it immediately. Even if the only production use case for FooObserver is that it is attached to window.Foo.Bar, this is still useful because setting up tests can be done with different configuration.

Do not modify objects you don't own

While the other examples are about preventing other code from causing problems with your code, this one is about preventing your code from causing problems for other code.

Many frameworks offer a reopen function that allows you to modify the definition of a previously defined object prototype (e.g. class). Don't do this in your modules, unless the same code defined that object (and then, you should just put it in the definition).

If you think class inheritance is a solution to your problem, think harder. In most cases, you can find a better solution by preferring composition over inheritance: expose an interface that someone can use, or emit events that can have custom handlers rather than forcing people to extend a type. There are limited cases where inheritance is useful, but those are mostly limited to frameworks.

;(function() {

// Bad: redefining the behavior of another module

window.Bar.reopen({

// e.g. changing an implementation on the fly

});

// Bad: modifying a builtin type

String.prototype.dasherize = function() {

// While you can use the right API to hide this function,

// you are still monkey-patching the language in a unexpected way

};

})();If you write a framework, for f*ck's sake do not modify built-in objects like String by adding new functions to them. Yes, you can save a few characters (e.g. _(str).dasherize() vs. str.dasherize()), but this is basically the same thing as making your special snowflake framework a global dependency. Play nice with everyone else and be respectful: put those special functions in a utility library instead.

Building modules and packages using CommonJS

Now that we've covered a few common bad practices, let's look at the positive side: how can we implement modules and packages for our single page application?

We want to solve three problems:

- Privacy: we want more granular privacy than just global or local to the current closure.

- Avoid putting things in the global namespace just so they can be accessed.

- We should be able to create packages that encompass multiple files and directories and be able to wrap full subsystems into a single closure.

CommonJS modules. CommonJS is the module format that Node.js uses natively. A CommonJS module is simply a piece of JS code that does two things:

- it uses

require()statements to include dependencies - it assigns to the

exportsvariable to export a single public interface

Here is a simple example foo.js:

var Model = require('./lib/model.js'); // require a dependency

// module implementation

function Foo(){ /* ... */ }

module.exports = Foo; // export a single variableWhat about that var Model statement there? Isn't that in the global scope? No, there is no global scope here. Each module has its own scope. This is like having each module implicitly wrapped in a anonymous function (which means that variables defined are local to the module).

OK, what about requiring jQuery or some other library? There are basically two ways to require a file: either by specifying a file path (like ./lib/model.js) or by requiring it by name: var $ = require('jquery');. Items required by file path are located directly by their name in the file system. Things required by name are "packages" and are searched by the require mechanism. In the case of Node, it uses a simple directory search; in the browser, well, we can define bindings as you will see later.

What are the benefits?

Isn't this the same thing as just wrapping everything in a closure, which you might already be doing? No, not by a long shot.

It does not accidentally modify global state, and it only exports one thing. Each CommonJS module executes in its own execution context. Variables are local to the module, not global. You can only export one object per module.

Dependencies are easy to locate, without being modifiable or accessible in the global scope. Ever been confused about where a particular function comes from, or what the dependencies of a particular piece of code are? Not anymore: dependencies have to be explicitly declared, and locating a piece of code just means looking at the file path in the require statement. There are no implied global variables.

But isn't declaring dependencies redundant and not DRY? Yes, it's not as easy as using global variables implicitly by referring to variables defined under window. But the easiest way isn't always the best choice architecturally; typing is easy, maintenance is hard.

The module does not give itself a name. Each module is anonymous. A module exports a class or a set of functions, but it does not specify what the export should be called. This means that whomever uses the module can give it a local name and does not need to depend on it existing in a particular namespace.

You know those maddening version conflicts that occur when the semantics of include()ing a module modifies the environment to include the module using its inherent name? So you can't have two modules with the same name in different parts of your system because each name may exist only once in the environment? CommonJS doesn't suffer from those, because require() just returns the module and you give it a local name by assigning it to a variable.

It comes with a distribution system. CommonJS modules can be distributed using Node's npm package manager. I'll talk about this more in the next chapter.

There are thousands of compatible modules. Well, I exaggerate, but all modules in npm are CommonJS-based; and while not all of those are meant for the browser, there is a lot of good stuff out there.

Last, but not least: CommonJS modules can be nested to create packages. The semantics of require() may be simple, but it provides the ability to create packages which can expose implementation details internally (across files) while still hiding them from the outside world. This makes hiding implementation details easy, because you can share things locally without exposing them globally.

Creating a CommonJS package

Let's look at how we can create a package from modules following the CommonJS package. Creating a package starts with the build system. Let's just assume that we have a build system, which can take any set of .js files we specify and combine them into a single file.

[ [./model/todo.js] [./view/todo_list.js] [./index.js] ]

[ Build process ]

[ todo_package.js ]The build process wraps all the files in closures with metadata, concatenates the output into a single file and adds a package-local require() implementation with the semantics described earlier (including files within the package by path and external libraries by their name).

Basically, we are taking a wrapping closure generated by the build system and extending it across all the modules in the package. This makes it possible to use require() inside the package to access other modules, while preventing external code from accessing those packages.

Here is how this would look like as code:

;(function() {

function require() { /* ... */ }

modules = { 'jquery': window.jQuery };

modules['./model/todo.js'] = function(module, exports, require){

var Dependency = require('dependency');

// ...

module.exports = Todo;

});

modules['index.js'] = function(module, exports, require){

module.exports = {

Todo: require('./model/todo.js')

};

});

window.Todo = require('index.js');

}());There is a local require() that can look up files. Each module exports an external interface following the CommonJS pattern. Finally, the package we have built here itself has a single file index.js that defines what is exported from the module. This is usually a public API, or a subset of the classes in the module (things that are part of the public interface).

Each package exports a single named variable, for example: window.Todo = require('index.js');. This way, only relevant parts of the module are exposed and the exposed parts are obvious. Other packages/code cannot access the modules in another package in any way unless they are exported from index.js. This prevents modules from developing hidden dependencies.

Building an application out of packages

The overall directory structure might look something like this:

assets

- css

- layouts

common

- collections

- models

index.js

modules

- todo

- public

- templates

- views

index.js

node_modules

package.json

server.jsHere, we have a place for shared assets (./assets/); there is a shared library containing reusable parts, such as collections and models (./common).

The ./modules/ directory contains subdirectories, each of which represents an individually initializable part of the application. Each subdirectory is its own package, which can be loaded independently of others (as long as the common libraries are loaded).

The index.js file in each package exports an initialize() function that allows that particular package to be initialized when it is activated, given parameters such as the current URL and app configuration.

Using the glue build system

So, now we have a somewhat detailed spec for how we'd like to build. Node has native support for require(), but what about the browser? We probably need a elaborate library for this?

Nope. This isn't hard: the build system itself is about a hundred fifty lines of code plus another ninety or so for the require() implementation. When I say build, I mean something that is super-lightweight: wrapping code into closures, and providing a local, in-browser require() implementation. I'm not going to put the code here since it adds little to the discussion, but have a look.

I've used onejs and browserbuild before. I wanted something a bit more scriptable, so (after contributing some code to those projects) I wrote gluejs, which is tailored to the system I described above (mostly by having a more flexible API).

With gluejs, you write your build scripts as small blocks of code. This is nice for hooking your build system into the rest of your tools - for example, by building a package on demand when a HTTP request arrives, or by creating custom build scripts that allow you to include or exclude features (such as debug builds) from code.

Let's start by installing gluejs from npm:

$ npm install gluejsNow let's build something.

Including files and building a package

Let's start with the basics. You use include(path) to add files. The path can be a single file, or a directory (which is included with all subdirectories). If you want to include a directory but exclude some files, use exclude(regexp) to filter files from the build.

You define the name of the main file using main(name); in the code below, it's "index.js". This is the file that gets exported from the package.

var Glue = require('gluejs');

new Glue()

.include('./todo')

.main('index.js')

.export('Todo')

.render(function (err, txt) {

console.log(txt);

});Each package exports a single variable, and that variable needs a name. In the example below, it's "Todo" (e.g. the package is assigned to window.Todo).

Finally, we have a render(callback) function. It takes a function(err, txt) as a parameter, and returns the rendered text as the second parameter of that function (the first parameter is used for returning errors, a Node convention). In the example, we just log the text out to console. If you put the code above in a file (and some .js files in "./todo"), you'll get your first package output to your console.

If you prefer rebuilding the file automatically, use .watch() instead of .render(). The callback function you pass to watch() will be called when the files in the build change.

Binding to global functions

We often want to bind a particular name, like require('jquery') to a external library. You can do this with replace(moduleName, string).

Here is an example call that builds a package in response to a HTTP GET:

var fs = require('fs'),

http = require('http'),

Glue = require('gluejs');

var server = http.createServer();

server.on('request', function(req, res) {

if(req.url == '/minilog.js') {

new Glue()

.include('./todo')

.basepath('./todo')

.replace('jquery', 'window.$')

.replace('core', 'window.Core')

.export('Module')

.render(function (err, txt) {

res.setHeader('content-type', 'application/javascript');

res.end(txt);

});

} else {

console.log('Unknown', req.url);

res.end();

}

}).listen(8080, 'localhost');To concatenate multiple packages into a single file, use concat([packageA, packageB], function(err, txt)):

var packageA = new Glue().export('Foo').include('./fixtures/lib/foo.js');

var packageB = new Glue().export('Bar').include('./fixtures/lib/bar.js');

Glue.concat([packageA, packageB], function(err, txt) {

fs.writeFile('./build.js', txt);

});Note that concatenated packages are just defined in the same file - they do not gain access to the internal modules of each other.

- [1] The modularity illustration was adapted from Rich Hickey's presentation Simple Made Easy

- http://www.infoq.com/presentations/Simple-Made-Easy

- http://blog.markwshead.com/1069/simple-made-easy-rich-hickey/

- http://code.mumak.net/2012/02/simple-made-easy.html

- http://pyvideo.org/video/880/stop-writing-classes

- http://substack.net/posts/b96642